Goat Production in Southern Africa and Zimbabwe (Focus on the Boer Goat).

According to FAOSTAT (2017), during the last decade there was an increase in goat production globally and currently there are more than 1 billion goats, with Africa contributing 36.2%, Asia 58.2%, Americas 3.5%, Europe 1.7% and Oceania 0.4%. In Southern Africa, goats are the second most important livestock species after cattle (Gwaze at al 2009). Approximately 96% of the world’s goat population is kept in developing countries, of which 64% are found in rural arid (38%) and semi-arid (26%) agro ecological zones (Gwaze et al 2009). The top-ten countries producing goat meat are all from Asia and Africa; indicating the importance of goat meat to people in resource-poor areas (Aziz 2010). In Africa, goat meat production has increased from 1.1 million tons in 2008 to 1.3 million tons in 2017 (FAOSTAT 2017); of which the majority is produced and consumed locally (within households) (Dubeuf 2004).

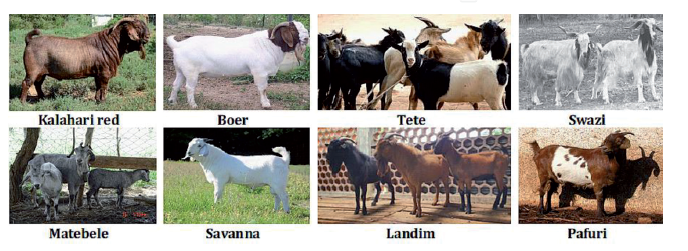

The Southern African goat population currently consists of approximately 38 million goats (Monau 2020). There are various goat breeds in Southern Africa, of which the Mashona, Matabele, Tswana, Nguni, Landim (Gwaze 2009) and Pafuri (Mataveia 2018) are the dominant ones. The goat populations in Southern Africa vary between countries: these variations in goats population are summarised in Table 1.1 below. Tanzania has the highest number with 18.9 million goats while Botswana has the smallest goat population (1.4 m) in Southern Africa (FAOSTAT 2020). FAO (2015) reported that there is approximately 576 goat breeds currently distributed across the world, with 17% of these in Africa. Although goats are found in all types of ecological zones, they are mainly concentrated in tropical, dry zones. As a result of natural selection, goats exhibit a wide range of physiological diversity

Table 1.1: showing the population of goats in Southern Africa.

Country | Population (in millions)

|

Angola | 4.7

|

Botswana | 1.4

|

Malawi | 8.9

|

Mozambique | 3.7

|

Namibia | 1.9

|

South Africa | 5.2

|

Eswatini | 2.4

|

Tanzania | 18.9

|

Zambia | 2.9

|

Zimbabwe | 4.7

|

Boer goat (Capra hircus) evolved in Southern Africa in the early 1990s from indigenous African goats kept by the Fooku, Namaqua and San tribes through cross breeding European and Indian bloodlines.. The name Boer came from the Afrikaans meaning farmer. The breed standards of the Boer Goat Breeder`s Association stipulate colour to be white with red head and blaze, pigmented skin and good, functional conformation. The Boer goat are hardy type , they grazer a wide range of plants, grasses and shrubs. Boer goat is considered to be one of the most desirable goat breeds for meat production (Casey et al., 1998). It has gained worldwide recognition for excellent body conformation, fast growing rate and good carcass quality.

It’s popularity as a meat goat breed soared during the last decade due to its availability in Australia, New Zealand and later in North America and other parts of the world. It has been demonstrated that Boer goats can improve productive performance of many indigenous breeds through cross breeding. It has a strong impact on the meat goat industry globally. There are five types of Boer goats recognized in South Africa according to South African Boer Goat Breeders’ Association (http://studbook.co.za/boergoat/stand.html). The ordinary Boer goats are animals with good meat conformation, short hair and a variety of color patterns. The long hair Boer goats have heavy coats and coarse meats.

Performance testing of Boer goats started in 1970 under South African Mutton and Goat Performance and Progeny Testing Scheme (Casey and Van Niekerk, 1988). Five phases of determination: doe’s characteristics, milk production, preweaning growth rate; postweaning growth rate; efficiency of feed conversion and body weight of male kids; postweaning growth rate of male kids under standardized conditions; qualitative and quantitative carcass evaluation of buck’s progeny;

are included in the testing. Combination of breed standards and performance testing is likely to be the better approach for the effective selection and improvement of Boer goats.

Figure1. 1: showing breeds of goats found in Zimbabwe.

Goat fattening systems

Traditional systems: This system generally depends on grazing natural or planted pastures with variable degrees of supplementation. Animals require a long period of time to attain market weight and condition. It is also associated with huge fluctuations in the weights and conditions of the animals depending on feed availability (Casey et al., 1998). This system can be improved to supply animals of acceptable condition to slaughterhouses for ultimate export. The conditioned animals may also go into a finishing operation targeted to supply the local market. Several improved traditional systems are in use, but they are not widespread.

Agro-industrial by-product based fattening: Fattening of sheep based on agro-industrial by-products is also practiced in some areas.This system can be promoted to similar areas where agro-industrial by-products are available. Fattening using agro-industrial by-products like sugar processing by-products is feasible in places for instance in parts where valuable feed resources such as molasses (from the sugar factories) and corn (grain and residue) are widely available (King, 2009). Protein sources like oilseed cakes can be purchased from nearby processing plants and/or forage legumes can be grown in the area. Brewery by-products are also available from the Delta Corporation brewery to serve as protein sources (Sikosana and Senda, 2010) .

Among all superior traits for goat meat production, heavier body weight and faster growing rate are the most notable in Boer goats. Birth weight of Boer kids ranges from 3 to 4 kg with male kids weighing about 0.5 kg heavier than female. Kids at weaning can weigh from 20 to 25 kg, depending on weaning methods and age (Cameron et al., 2001). At 7 month of age, bucks weigh about 40 to 50 kg while doelings weigh about 35 to 45 kg. At yearling, bucks weigh 50 to 70 kg and doelings weigh 45 to 65 kg. Mature weights for bucks and does are 90-130 kg and 80-100 kg, respectively (King, 2009). These body weights measurements can be variable because of other underlying factors such as genetics, nutrition, health and disease outbreaks, breeding age and method, and general management system.

Because of their desirable genetic traits for meat production, Boer goats have successfully improved productive performance of indigenous breeds through cross breeding. Most notable improvement include birth weight, growth weight, weaning weight, breeding weight, mature weight, kidding rate, carcass quality (Ssewannyana et al., 2004). Boer and Spanish crosses were reported to have higher dry matter intake, average daily gain than Spanish goats (Cameron et al., 2001). During the 15 week trail from post weaning to 24 weeks of age, average daily gain was increased by 30% through the cross breeding between Boer and Spanish goats, but the 154 g/day gain was below the 200 g/day normally observed in Boer goats. Dry matter intake was also higher in Boer and Spanish cross.

Feed efficiency, average daily gain/dry matter intake, was higher in Boer and Spanish cross. In another study, birth weight, weaning weight and average daily gain were improved by crossing Spanish, Nubian, or Angora with Boer goats (Brown and Machen, 1995). According to Prieto et al. (2000) feeding of high protein diets does not increase the rate of gain in Boer and Spanish cross goats. As expected they average daily weight gain and feed efficiency were increased by the cross breeding. But feeding diets containing 18 and 24% crude protein did not improve weight gain and feed efficiency. Results of their study implied that over nutrition might not increase economic return for Boer crosses.

Farmers reported source of meat, manure, income and symbol of wealth as the major reasons for keeping goats in that order. All these have been reported before (Rumosa Gwaze et al., 2009; Dossa et al., 2015), in addition to skins, cashmere and mohair (Haenlein and Ramirez, 2007). Barter trade (Morand-Fehr et al., 2004) was not reported in this study. Goats are also used for cultural purposes such as bira vernacular for brewing of beer in remembrance of the deceased, kuchenura (memorial services), kupira (dedication of spirit mediums on bucks), kurasira (exorcism of evil spirits) and for religious purposes by different ethnic groups. The important role played by goats in traditional ceremonies was noted by Simela and Merkel (2008). Homann et al. (2007) reported cash income or milk as the main reasons for keeping goats in some districts in the Southern arid parts of Zimbabwe. Milk was also ranked high in that study, which is contrary to the low ranking assigned to milk in this study. The importance assigned to goat milk is dependent on cultures. Respondents indicated that goats are rarely milked in Katerere area due to poor feed resources in the area, and that people consider it taboo. About 11.3% of the households indicated that they milk their goats. Of these, the majority (75%) fed the goat milk to infants, while a small proportion (5%) indicated whole family

Challenges encountered in Boer goat production

The major factors constraining goat production are high mortality rates, predation and inbreeding. Hyenas and wild dogs are the most common predators of goats in Zimbabwe. Disease incidences are particularly common in February and March, which marks the mid-rainy season in most parts of Zimbabwe. The rainy season is conducive for internal parasite infestation and, thus, contributes to ill health of goats. Goat kids are the most vulnerable to both predation and disease attacks such as pulpy kidney if not vaccinated. Mass vaccination is not common and usually is only done when there is a major outbreak in the country. Mortality of Kids due to predation can be reduced by providing appropriate housing for kids particularly when the rest of the flock is released to forage. Appropriate housing reduces mortality and facilitates effective animal health management (Homann et al., 2007). Disease outbreaks, following the rainy season, are the most notable contributor and high kid mortality rates (45%) in the rainy season have been attributed to high populations of biting insects and ticks (Sikosana and Senda, 2010).

Due to poor legislation of goat breeding, there is now an increase on inbreeding by most farmers who are not registered as stud breeders or involved in any breeding association leading to poor dissemination of genetics hence affecting other traits of economic importance such as weaning weights and carcass quality. Ideally, dipping should be done weekly and fortnightly in summer and winter, respectively (Sikosana and Senda, 2010) but farmers are failing to purchase dipping chemicals and effectively dip their goats. Goats are raised under the extensive rearing system where flocks are driven into the grazing area and mountains, hence, no controlled breeding. This provides for an open mating system that does not enable for the selection of productive animals (van Rooyen and Homann, 2008). This practice, coupled with the fact that these farmers do not introduce new genetics by way of buying bucks from other villages, promotes inbreeding.

According to Webb and Mamabolo(2004), indigenous goats are a valuable genetic resource owing to their ability to adapt to harsh climatic conditions, utilizing limited and often poor quality feed resources and their natural resistance to a range of diseases, much needs to be done to improve flock productivity under smallholder farmer management. More so High feed costs are being observed in the goat industry. If a farmer wants to venture into meat goat fattening, the farmer has to consider making feed for himself since the commercial grade feeds are a bit expensive and required in bulky volumes to attain higher carcass quality and quantity after slaughter. More so when making your own feeds the raw materials such as Soya bean, soya bean meal, sun flower cake and cotton seed cake are being sold at premium prices by oil refinery companies. In addition, most farmers lack the basic knowledge on how to make the feeds for meat goats since goats tend to be selective on what they consume.

Conclusively goat production in Southern Africa and Zimbabwe has been on the rise for the past 5 years in line with Vision 2030.

Aziz M. 2010 Present status of the world goat populations and their productivity. Lohmann Information.

Boogaard B, Moyo S. 2015 The multifunctionality of goats in rural Mozambique: Contributions to food security and household risk mitigation. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Report No.: ILRI Research Report 37

Brown, R. and J. and R. Machen. 1997. Performance of meat goat kids sired by Boer bucks. Texas Agricultural Extension Service.

Cameron, M. R., J. Luo, T. Sahlu, S. P. Hart, S. W. Coleman, and A. L. Goetsch. 2001. Growth and slaughter traits of Boer x Spanish, Boer x Angora, and Spanish goats consuming a concentrate-based diet. J. Anim. Sci.

Casey N. H. and W. A. van Niekerk. 1988. The Boer Goat. I. Origin, adaptability, performance testing, reproduction and milk production. Small Rumin. Res.

Dossa, L.H., Sangaré, M., Andreas Buerkert, A., Schlecht, E., 2015. Production objectives and breeding practices of urban goat and sheep keepers in West Africa: regional analysis and implications for the development of supportive breeding programs. SpringerPlus 4.

Food and Agriculture Organization Statistics (FAOSTAT). 2017.

Gall C. 1981 Goat Production. London: Academic Press

Gwaze, F.R., Chimonyo, M., Dzama, K., 2009. Communal goat production in Southern Africa: a review. Trop. Anim. Health Prod.

Haenlein, G.F.W., Ramirez, R.G., 2007. Potential mineral deficiency on arid rangelands for small ruminants with special reference to Mexico. Small Rumin. Res. 68, 35–41.

Homann, S., van Rooyen, A.F., Moyo, T., Nengomasha, Z., 2007. Goat production and marketing: baseline information for semi-arid Zimbabwe. P. O. Box 776, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe, Inter. Crop. Res. Inst. Semi-Arid Trop.

King F J M 2009 Production parameters for Boer goats in South Africa. MSc. Thesis, University of the Free State, Free State, South Africa

Kosgey I, Rowlands G, van Arendonk JA, Baker R. 2008 Small ruminant production in smallholder and pastoral/ extensive farming systems in Kenya. Small Ruminant Research.

Liu J, You L, Amini M, Obersteiner M, Herrero M, Zehnder AJ 2010. A high-resolution assessment on global nitrogen flows in cropland. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Madibela O, Mosimanyana B, Boitumelo W, Pelaelo T. 2002. Effect of supplementation on reproduction of wet season kidding Tswana goats. South African Journal of Animal Science.

Morand-Fehr, P., Boutonnet, J.P., Devendra, C., Dubeuf, J.P., Haenlein, G.F.W., Holst, P.,

Mowlem, L., Capote, J., 2004. Strategy for goat farming in the 21st century. Small Rumin. Res

Midgley S, Dejene A, Mattick A. 2012 Adaptation to climate change in semiarid environments: experience and lessons from Mozambique. Environment and Natural Resources Management Series, Monitoring and Assessment- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations.

Oluwatayo IB, Oluwatayo TB. 2012 Small ruminants as a source of financial security: a case study of women in rural Southwest Nigeria. Institute for Money, Technology and Financial Inclusion (IMTFI), Working Paper.

Onzima RB, Gizaw S, Kugonza DR, van Arendonk JAM, Kanis E. 2018 Production system and participatory identification of breeding objective traits for indigenous goat breeds of Uganda. Small Ruminant Research.

Peacock C. 2005. Goats—A pathway out of poverty. Small Ruminant Research.

Sones K, Grace D, MacMillan S, Tarawali S, Herrero M. 2013 Beyond milk, meat, and eggs: Role of livestock in food and nutrition security. Animal Frontiers.

South African Boer Goat Breeders’ Association http://studbook.co.za/boergoat/stand.html.

Sikosana, J.L.N., Senda, T.S., 2010. Goat Farming as a Business: A Farmer’s Manual to Successful Goat Production and Marketing. Department of Agricultural Research and Extension Matopos Research Station, Zimbabwe.

Simela, L., Merkel, R., 2008. The contribution of chevon from Africa to global meat production. Meat Sci.

.Ssewannyana E, Oluka J and Masaba J K 2004 Growth and performance of indigenous and crossbred goats, Uganda. Journal of Agricultural Sciences.

Rooyen, A., Homann S., 2008. Enhancing incomes and livelihoods through improved farmers’ practices on goat production and marketing: Proceedings of a workshop organized by the Goat Forum, Inter. Crop. Res. Inst. Semi-Arid Trop,

Webb, E.C., Mamabolo, M.J., 2004. Production and reproduction characteristics of South African indigenous goats in communal farming systems. S. Afr. J. Anim. Sci.